|

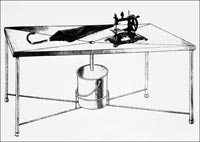

Ultimately, Homer was describing a known distant place north of the Black Sea, in the heart of the Ukraine or suchlike steppe. Once in this kind of grassland the oar is mistaken as athereloigón, which means winnowing fan, he should stop, plant his oar in the ground and make of it a makeshift altar to Poseidon, thus introducing the god of the sea to a people who are unversed in him. Before this altar, Odysseus must make sacrifice, after which he is to return to Ithaca, until he leaves again to die from the sea. Stoddart masterfully elaborates on the scenes inspired by the prophecy to create a simple allegory. The figure at the extreme left of the large panel is the good swineherd Eumaeus, who is the stalwart advocate of Odysseus’ return to Ithaca. The old woman seen immediately next to him, behind Penelope, is Eurycleia, the wet nurse of Odysseus, who first recognises the hero on his arrival at the Palace by the boar-tusk scar on his thigh. These two figures, together with a notional offspring of Argos the dog, represent those common people of low socio-economic station and scant education that recognize truth when they see it, and act on moral impulses rather than the expedient imperatives than the suitor type typically does. Thus, in this allegory, they represent those people who, when asked about art say that they know nothing about it, but know what they like or like what they know. Odysseus, representing classical art, following the Trojan War, which alludes to the slaughter of the Great War, travels to a region completely alien to Greece, where the customary things are entirely unknown, that is modernism. At the other end, the male figure is Telemachus and the female ones those who will follow Odysseus to the outlandish regions. They represent the traditionalists who travelled with classicism into the wasteland and met those saltless barbarians in the galleries, reception halls, and the salons of hardline contemporaneity of New Bond Street. The Sacrifice panel simply shows Odysseus and the stranger who asks about the winnowing fan. Before the stranger is his little son, in a barbaric crotchless trouser exposing his genitals like in Donatello’s Amor-Attis of 1440 (Bargello, Florence), whose symbolical mystery is too arcane to perceive nowadays. The oar, emblematic of all things Grecian, is set up in a culture temporally and geographically distant from its original conditions on Richard Green gallery, the very building upon which this allegory is played out. In view of the extreme lengths modern art took to distance itself from its classical origins in Greece, the prophecy of Tiresias is of relevance.Odysseus’ oar set in the middle of an endless prairie, is emblematic of utmost  pathos, and as image is comparable to the well-known verse in Comte de Lautréamont’s 1868 Song VI, describing a young boy, “beautiful […] as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella” οτι(Lautréamont 1938:256). This erotic verse, which Man Ray illustrated in his 1933 Homage to Lautréamont [Fig. 3], was often used by André Breton as a paradigm of Surrealist dislocation and had a major influence on modern art, especially as Duchamp’s aided readymades exemplify. pathos, and as image is comparable to the well-known verse in Comte de Lautréamont’s 1868 Song VI, describing a young boy, “beautiful […] as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella” οτι(Lautréamont 1938:256). This erotic verse, which Man Ray illustrated in his 1933 Homage to Lautréamont [Fig. 3], was often used by André Breton as a paradigm of Surrealist dislocation and had a major influence on modern art, especially as Duchamp’s aided readymades exemplify. |