|

Actually, however, it is a shovel used also to throw salt in advance of a snowfall. This shovel’s probable relation to the Homeric Winnowing Fan endows it with qualities in keeping with Duchamp’s blasphemous iconoclastic program. The collage of the 1915 readymade shovel against a photograph of his New York studio, around 1920, as he retouched it for Box in a Valise of 1942, shows it stagily suspended from a hook in the air as a deus ex machina. Its verticality echoes the upright planting of Odysseus’ oar, standing for the resolution of the struggle in rest. Its downward orientation, a reversal of its possible reference, may serve as yet another layer of removal from the original object in the artist’s mind. What matters most, however, is the fine irony in the artistic rationale that Duchamp’s emblem of relocation appropriates Odysseus’ trophy of dislocation.

The occult significance of salt may further be figured by the myth of the contest between Athena and Poseidon for the patronage of Athens, as represented on the west pediment of the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis. Athena won by her gift of the olive tree, over Poseidon, who offered a salty spring. The bipolarity of the two gifts is clear. The olive tree associates with the feminine trait of proactive thinking offering a respected and useful plant that is rooted on earth, emblematic of the home. On the other hand, the spring is a masculine symbol of perpetual change, fluidity and instability, and its salty water unmistakably refers to the sea. Therefore, the salt is emblematic of all things associated to the seafaring travels of the sailor either as a merchant, warrior or adventurer.

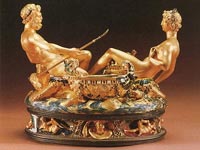

The link of salt to the sea and its god, combined with a high value and esoteric meaning, is attested by Benvenuto Cellini’s most remarkable work, his Saltcellar of 1543 [Fig. 6], an ornamental salt and pepper holder for the King of France, Francis I. It was made of gold, ebony and enamel in the style of the School of Fontainebleau and of the late Renaissance Italian Mannerism. It allegorically portrays Ocean and Earth (Symonds 1901:II.36), represented by salt and pepper. The former is personified by the form of Poseidon, born by four seahorses, holding a trident in his right hand, and seaweed and mussels in his left hand, with a boat at his side, in which to receive the salt. The latter appears as Gaia, perched on an elephant, pressing her nipple with her left hand, and having her right hand holding a cluster of fruit, by a small Ionic temple on her side, in which to keep the pepper. The legs of the two gods are intertwined, the way Cellini imagined the limbs of land and sea to be conjoined, symbolizing their unity. Additional reclining figures, representing winds and the times of day, are carved into the base upon which the whole object stands. However, the fact that the salt is destined for a vessel floating on waves in Poseidon’s care and the pepper for a temple fixed on land by the side of Gaia evokes Cellini’s broader agenda about gender differences if not a segmentation scheme. The link of salt to the sea and its god, combined with a high value and esoteric meaning, is attested by Benvenuto Cellini’s most remarkable work, his Saltcellar of 1543 [Fig. 6], an ornamental salt and pepper holder for the King of France, Francis I. It was made of gold, ebony and enamel in the style of the School of Fontainebleau and of the late Renaissance Italian Mannerism. It allegorically portrays Ocean and Earth (Symonds 1901:II.36), represented by salt and pepper. The former is personified by the form of Poseidon, born by four seahorses, holding a trident in his right hand, and seaweed and mussels in his left hand, with a boat at his side, in which to receive the salt. The latter appears as Gaia, perched on an elephant, pressing her nipple with her left hand, and having her right hand holding a cluster of fruit, by a small Ionic temple on her side, in which to keep the pepper. The legs of the two gods are intertwined, the way Cellini imagined the limbs of land and sea to be conjoined, symbolizing their unity. Additional reclining figures, representing winds and the times of day, are carved into the base upon which the whole object stands. However, the fact that the salt is destined for a vessel floating on waves in Poseidon’s care and the pepper for a temple fixed on land by the side of Gaia evokes Cellini’s broader agenda about gender differences if not a segmentation scheme.

|